いつもあたたかいご支援ををいただき、本当にありがとうございます。

今年も残すところあと3日となりました。

2022年は皆さまにとってどのような年でしたか?ルーム・トゥ・リードにとっては大きな節目の年になりました。

ルーム・トゥ・リードは、"子どもの教育が世界を変える"との信念に基づき2000年に設立され、非識字やジェンダー間の不平等のない世界を実現するために活動する国際NGOです。

11月17日からスタートした、アジア・アフリカ諸国の低所得コミュニティに住む子ども達2,000名に教育というギフトを届けるキャンペーン、Action for Education2022~エデュケーション・イコール~。

日本全国から、そして海外からも合計203名の方々よりご寄付をいただきました!12月17日のアビームコンサルティング様からのダブルマッチング、12月23~25日のリージョナルボードの正直知哉・ゆり夫妻からのトリプルマッチング分を加えると、26,372,764円*もの寄付金をお預かりさせていただき、これにより、目標を大幅に上回る5,274名*もの子ども達をサポートすることができました!

(*2023年1月に情報を更新いたしました。)

ルーム・トゥ・リード・ジャパンでは、アジア・アフリカ圏の低所得コミュニティに住む子ども達2,000名に教育というギフトを届けるためのAction for Education2022~エデュケーション・イコール~を実施中です。

現在までに、目標の1,000万円に対しおよそ500万円のご寄付をいただいており、1,000人の子ども達のサポートが実現できています。あと、500人の子ども達にクリスマスギフトを贈りたいと思っています!

(なお、こちらには12月17日にアビームコンサルティングさんが行ってくださった500万円のマッチングは入っておりません。キャンペーン後にマッチング分もすべて集計した結果をご報告いたします)。

12月23~25日のご寄付は、なんと3倍のインパクトになります!

本日よりクリスマスまでの3日間、リージョナルボードの正直知哉・ゆり夫妻、そして匿名の寄付者により、この期間の皆さんからの寄付が「3倍」になるトリプルマッチング(上限:1,500万円まで)を実施します!

例えば、ひとりの子どもの支援するために必要な5,000円寄付していただくと、3倍の15,000円がマッチングされ、3名の子ども達をサポートすることができます。

ルーム・トゥ・リード・ジャパンへのご寄付は税制控除となります!

クレジットカードでのご寄付はこちらからお願いします。

(VISA、Maste、AMEXで承っております)

銀行振込でのご寄付はこちらからお願いします。

三菱UFJ銀行 虎ノ門支店 普通 0425102

トクヒ)ル-ム トウ リ-ド ジヤパン

※お振込の際には、ご入金者を特定できるよう必ずこちらのフォームかjapan@roomtoread.orgまでお知らせください。

◆リージョナルジョナルボードの正直ゆりからのメッセージ動画はこちらからご覧ください。

◆ルーム・トゥ・リードCEO のギータ・ムラリからのメッセージ動画はこちらからご覧ください。

教育への投資によって、子ども達の人生とコミュニティ全体の未来を変えることができます。

全ての子ども達が平等な教育を受けられる世界をともに目指しませんか?

ご支援を心からお待ちしております!

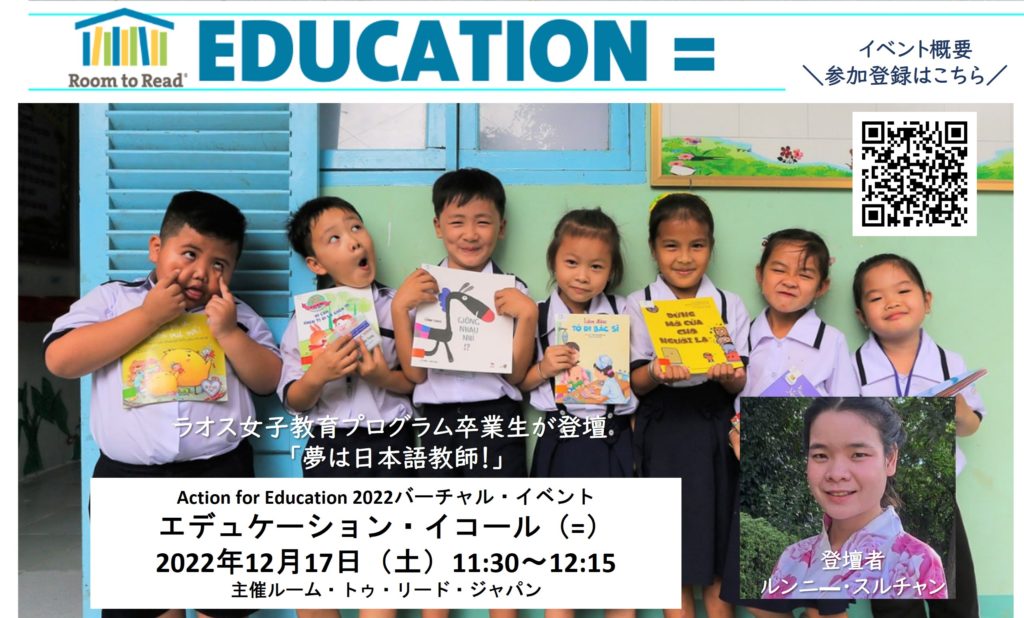

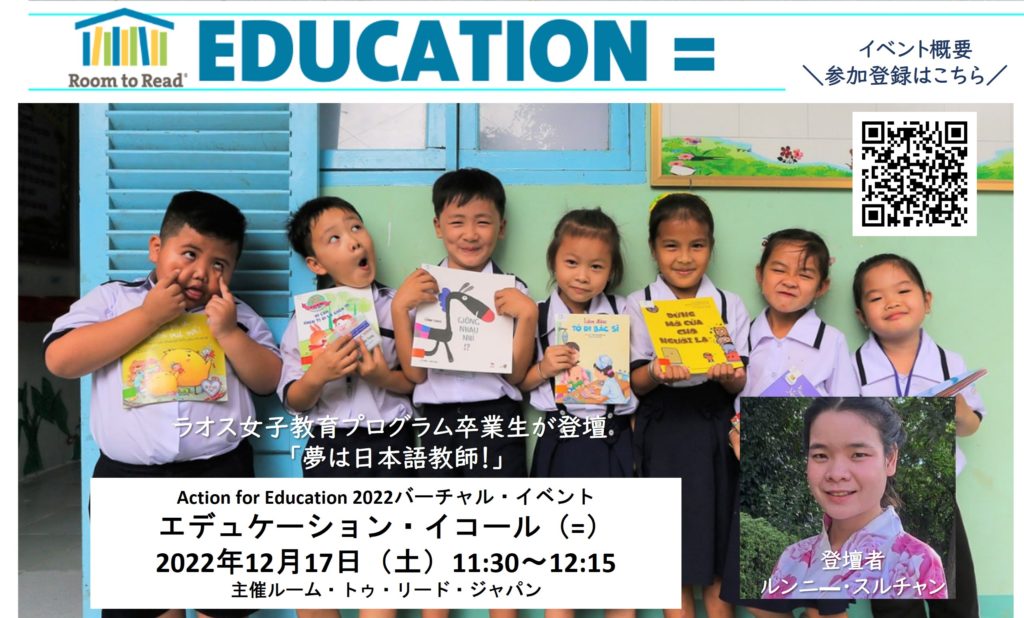

一人ひとりが自分にできるアクションを起こし、子ども達2000名に教育というクリスマスプレゼントを贈る年末寄付キャンペーンAction for Education 2022を開催しています。今年のテーマは「エデュケーション・イコール」。 12月17日(土)11:30より45分間のキックオフイベントを開催します。

当日はピムコジャパンリミテッド様から運営サポートをいただき、ルーム・トゥ・リードのCEOであり、クレディ・スイスとタイム社主催「2022 Women of Impact」でも表彰されたギータ・ムラリの出演、ラオスの女子教育プログラムを卒業し、日本語教師を目指して留学中のルンニー・スリチャンの登壇、事前に寄せられたご質問への回答など盛りだくさんの内容でお届けします。

ウェビナー形式(皆様のお顔は投影されません)で開催いたしますので、ぜひお気軽にご参加ください!

Action for Education 2022 – エデュケーション・イコール

\オンラインイベント参加登録はこちらから/

◆概要

日時:2022年12月17日(土)11:30~12:15

開催方法:ZOOMウェビナー

参加費:無料

参加登録:登録フォーム

運営サポート:ピムコジャパンリミテッド

備考:

・画面には登壇者のみ投影されます。お気軽にご参加ください。

・ルンニーへの質問はjapan@roomtoread.orgまで12/16までにお寄せください。

◆プログラム(予定)

11:30~11:40

・オープニング: 正直知哉(ルーム・トゥ・リード リージョナルボードチェア)

・2022年活動報告および支援状況:ギータ・ムラリ(ルーム・トゥ・リード CEO)

11:40~12:00

「私にとっての教育」

・講演者:ルンニー・スルチャン(ラオス女子教育プログラム卒業生)

・進行・質疑応答:正直ゆり(ルーム・トゥ・リード リージョナルボード、ルーム・トゥ・リード・ジャパン共同理事長)

12:00~12:15

・日本での活動紹介(ルーム・トゥ・リード・ジャパン事務局長 松丸佳穂)

・クロージング

◆登壇者

ギータ・ムラリ博士 (ルーム・トゥ・リード CEO)

2009年ルーム・トゥ・リード入局、2018年よりCEO。世界中にあるルーム・トゥ・リード約60拠点での活動、政府・学校・地域との連携を通じて、質の高い識字教育と男女平等プログラムの実施をけん引。1,600人の職員、理事会、寄付者、ボランティア支部のグローバルネットワーク責任者。2022年Woman of Impact受賞。

正直知哉 (ルーム・トゥ・リード リージョナルボードチェア)

ルーム・トゥ・リード リージョナルボードチェア、ピムコジャパンリミテッドの日本における代表者 兼 アジア太平洋共同運用統括責任者。大阪大学(工学学士号および工学修士号)、ボストン大学でMBAを取得。住友ファイナンス・ インターナショナル、ゴールドマン・サックス・アセット・マネジメントを経て現職。投資業務経験33年。2017年よりルーム・トゥ・リードの活動を支援。

参考:企業・団体 SDGsへ連携を(日本経済新聞 寄稿文)

正直ゆり(ルーム・トゥ・リード リージョナルボード、ルーム・トゥ・リード・ジャパン共同理事長)

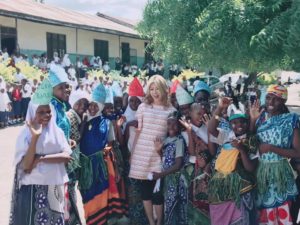

上智大学比較文化学部、ロンドン大学大学院修士課程修了、野村證券を経て現在まで数々のNPO、NGO、社会貢献活動を支援。2017年よりルーム・トゥ・リードの活動を支援。ルーム・トゥ・リードが活動を行っている国に数多く訪問し、多くの子ども達や地域の人々と交流を持つ。「子ども達に教育の幸せを届け、社会にポジティブなインパクトもたらす事を目指しています!」

ルンニー・スリチャン

ルーム・トゥ・リード・ラオス女子教育プログラム卒業生。ウドムサイ県の少数民族出身。小学校5年生から女子教育プログラムに参加。野口英世の伝記に感銘を受け、女性の大学進学率がわずか15%のラオスにおいてラオス国立大学文学部日本語学科へ進学。日本語教師を志し東京外国語大学の留学枠を勝ち取るも2020年コロナ禍で渡航停止、その後も最愛の家族を亡くすなど多くの試練が。それでも諦めることなく勉強を続け2022年国際交流基金が提供する海外日本語教師基礎研修生に合格。2022年9月から来日、夢に向かって猛勉強中。

参考:オンラインイベント開催に寄せて(事務局長松丸より)

参考:ルンニ―からのメッセージ(日本語)

コロナ禍から3年を経て、サッカーワールドカップでの日本代表の活躍など、明るいニュースも届いています。

ぜひ、2022年の締めくくりを共にお祝いできればと思います。

12月17日に皆様にお会いできることを楽しみにしております!

一人ひとりが自分にできるアクションを起こし、子ども達に教育というクリスマスプレゼントを贈る年末寄付キャンペーンAction for Education2022を今年も開催致します。今年こそは皆様とリアルでお会いしたい!とイベント場所を決めて準備を重ねていたのですが、「第8波」報道もあり、迷った末にオンラインにてキックオフイベントを開催することに致しました。

2022年のテーマはエデュケーション・イコール。

ここ数年のコロナ禍に加えて、今年はウクライナをはじめとする戦争、スリランカでの経済危機、パキスタンの洪水に例を見る自然災害の増加など、子ども達に深刻な学習損失が発生しています。今年も、クリスマスまでに2000名の子ども達へ教育を贈ることを目標にアクションをおこします。

イベントでは、皆様とともに達成できた数々の成果とともに、現状についてもご報告いたします。また、今回はスペシャルゲストが登壇予定です! 過去のオンラインイベントにご参加くださった方はご記憶の方もいらっしゃるかもしれませんが、ラオスからビデオメッセージを送ってくれた女子教育プログラム卒業生ルンニー・スリチャンが、なんと東京のスタジオから生出演予定です!

参考:ルンニ―からのメッセージ(日本語)

そうです! ルンニーは、コロナ禍で一度は中断されてしまった来日するという夢をついに叶えたのです。

ウドムサイ県の少数民族出身のルンニーは、小学校5年生からルーム・トゥ・リードの女子教育プログラムに参加し、高校卒業後、見事、ラオス国立大学に入学しました。私が彼女に初めて会ったのは2018年2月。ルンニーが大学1年生で、日本語を学び始めたばかりの頃でした。支援企業の社員の皆さんとともにラオスのビエンチャンに訪問したのですが、日本人が来ると聞いて、覚えたての日本語で一生懸命スピーチをしてくれました。

それ以降もルンニーとは定期的にオンラインで話す機会がありました。難関を突破し、自分の手で勝ち取った日本への留学がコロナの影響で閉ざされ、卒業論文を執筆中には最愛の家族を亡くすなど、ルンニーには常に多くの試練がありました。でも、彼女はいつも前向きでした。いつか日本に行ける日を信じ、大学卒業後も勉強を続けていたのです。

ルンニーのひたむきさと落ち着いた姿に、私は多くを学び励まされました。自分自身が何のためにこの仕事をしているのか―。教育がもたらす希望を、彼女はまさに体現していたのです。

ぜひ、ルンニーの生の言葉から、皆さまの毎年のご支援が実際にどのようなインパクトをもたらしているのか。また、改めて皆さまにとっての教育とは何か、など、一緒に考える機会にしていただければと思います!

Action for Education 2022 – エデュケーション・イコール

\オンラインイベント参加登録はこちらから/

◆Action for Education 2022「エデュケーション・イコール」オンラインキックオフイベント

12月17日(土)11:30~12:15

参加方法:Zoomウェビナー

参加費:無料

参加登録:登録フォーム

備考:画面には登壇者のみ投影されます。ぜひ、お気軽にご参加ください。

登壇者:

ギータ・ムラリ(ルーム・トゥ・リード CEO)

正直知哉(ルーム・トゥ・リード リージョナルボード チェア)

正直ゆり(ルーム・トゥ・リード・リージョナルボード、ルーム・トゥ・リード・ジャパン共同理事長)

ルンニー・スルチャン(ラオス女子教育プログラム卒業生)

ぜひお友達をお誘い合わせのうえご参加ください。

オンラインではありますが、皆さまとお会いできることを楽しみにしています!!

感謝をこめて。

ルーム・トゥ・リード・ジャパン事務局長

松丸佳穂